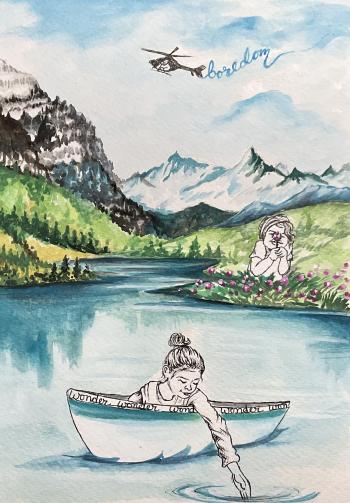

Wonder Increases As Speed Decreases

Indulge me for a moment: let’s do a short thought experiment. We’ll compare two different mornings. On one, you’ll fly coast-to-coast, a five hour journey. Imagine yourself in the high-backed seat, being flung across hundreds of miles as the hours creep by. What feeling comes to mind? Boredom. The need for distraction is intense: a book, a movie, a crinkly bag of peanuts. Now, imagine another morning. Pick any point along the flight path and spend those same five hours in a stroll across fields, urban neighborhoods, or forests. What mental states come to mind? Not boredom, for sure. Engagement or curiosity, perhaps?

So, wonder increases as speed decreases. As we cover less ground, we uncover more; as we narrow the field of view, our horizons expand. Monks from the East know this: in one breath is Every Thing. Poets from the West know this also: says Blake, “…a World in a Grain of Sand.” But this truth is seen not just by meditators and mystics. Almost all literature is built on the same understanding. Tolstoy may have opened Anna Karenina with the claim that, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” but the next nine hundred pages are not about “all” and “every,” instead they examine the particularities of just a few. Through an intense focus on a handful of people, Tolstoy painted a more comprehensive picture of human relationships than could any all-covering textbook.

I took this insight to the woods to see what I could learn. I spent a year watching one square meter of forest, giving my attention to the life of this small circle of leaves. The patch of forest became my window into the natural world. During that year, I saw a parade of salamanders, beetles, worms, fungi, flowers, songbirds, ants, caterpillars, shrews, and leaves. The activity present in a tiny patch of forest was astonishing. More astonishing, though, was what I could not see. In one half handful of soil, a billion microbes live out their lives. We humans can’t see them, but we can smell their warm odors in the soil and see their action as autumn’s leaves gradually sink down into the earth. Without this hidden “99%,” the rest of life would not be possible.

Sitting in the forest for hundreds of hours opened my senses. I connected to the variegated physicality of the world in ways that enriched my experience and helped me better understand the workings of the forest. The quality of light, for example, varies dramatically through the year. In the summer, photon-greedy tree leaves steal most of the colors from the light spectrum, creating a greeny-yellow world below the forest canopy. A red-feathered bird therefore looks dusky and dull in summer – trees have stolen the red light, so none is available to bounce off the bird’s plumage. But if the bird positions itself in an unimpeded ray of sunlight, its colors kindle into a brilliant blaze. In autumn, the trees release their hold and the forest’s palate opens up. The herbaceous plants on the forest floor put on a surge of growth to make use of this new-found richness.

We find wonder in the world not by hurling ourselves across the planet on airplanes in search of wonderful places. Rather, wonder comes when we give our attention to the world, starting with our homes. By coming to our senses, attending to the smell, touch, sounds, and sights around us, we can start to hear the remarkable stories of our world. Don’t take my word for it, though. Pick a small area wherever you live – a tree in a park, a small circle of land behind your house, a stream behind an apartment complex – and honor it with your attention. Don’t expect drama or enlightenment, just watch quietly over the months and see the world come alive.

David Haskell is the author of The Forest Unseen. He lives in Sewanee, Tennessee, where he and his wife run Cudzoo Farm, a small homestead producing hand-crafted goat milk soaps.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: How do you relate to the notion that wonder increases as speed decreases? Can you share a personal story of a time you slowed down and realized an increase in wonder? What helps you build the commitment to watch quietly?

Add Your Reflection

15 Past Reflections

On Mar 26, 2023 Babusankarasubramanian wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Sep 4, 2022 Jay Sheth wrote :

I started to walk slowly without thinking or worrying about how i was appearing outside. It was late evening and dark anyway.

As I slowed my walk, my breathing, I could sense calming and aligning with my footsteps. I felt massaged in my feet as I walked slowly putting feet properly on the ground.

By the time I reached hostel, I felt renewed by my walking activity and felt calm and serene. It felt, the word is .... Deeply satisfying.

I was practising Tantra Techniques since 3 to 4 months then. This moment was culmination of all effort of past 4 months into an incredible experience of peace.

Post Your Reply

On Aug 31, 2022 badri wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 31, 2022 smok wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 30, 2022 Shyam wrote :

Slowing down , spending quality time on the way , reveals so many hidden truths, both outside and inside of our selves.

Post Your Reply

On Aug 30, 2022 JC wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 30, 2022 Kate Mackrell wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 30, 2022 Bryn wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 29, 2022 Annie wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 28, 2022 Ted wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 27, 2022 David Doane wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 26, 2022 Naren Kini wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 26, 2022 Jagdish P. Dave wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Aug 26, 2022 susan schaller wrote :

and selfless service possible.

Post Your Reply