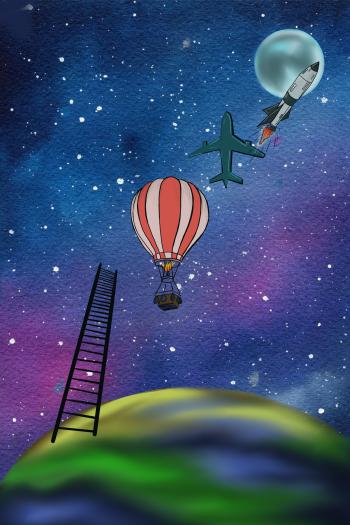

Longer Ladders Don't Get You To The Moon

Sundials came into being over 3,000 years ago, telling time-based on shadows cast by the sun. But they were thrown off by variations in the length of days and by differences in latitude. Geometry was used only partially successfully to fix these problems, and of course sundials were useless at night.

Clocks based on gravity (instead of shadows) attempted to fix these problems. Water clocks — water dripping through a narrow opening — could be used whatever the season or latitude. But they were fragile, not easily transportable (necessary for navigation), and difficult to use and to produce precisely enough to tell good time. Hourglasses, still based on gravity (but now using sand instead of water), solved some of these problems, but still weren’t particularly accurate or easy to standardize.

At least not compared to the next generation of clocks, which relied on springs and gears.

Fast forward to today and there are atomic clocks, that are incredibly accurate and reliable, which work by counting electrons moving back and forth nearly 10 billion times per second.

Notice that each advance is not only more accurate and useful, it’s also based on an entirely different principle than its successors: the rotation of the earth; gravity; mechanics (physics); and the oscillation of atoms.

And this is how non-incremental changes in technology occur: applying new principles.

You can’t keep tweaking a technology and get better and better results. Eventually a principle must change. Longer and longer ladders don’t get you to the moon.

The economy, though it's gigantic, is itself is a technology. [...] And maybe it needs new principles. Different principles by which the economy might operate so that it benefits more people and respects that we are a part of, not apart from, nature.

What might those look like?

What’s in it for me? underlies most economic thinking. Economists dating back to Adam Smith have argued that acting from self-interest will produce a vibrant economy for all. Perhaps we should be asking What’s in it for us? to bring things into balance.

It’s not personal, it’s strictly business: As uttered by Michael Corleone in the Godfather, this principle explains how to keep score: by results and outcomes. Perhaps better guidance is to focus on relationships and what is personal in how we operate and let results flow from there.

Survival of the fittest: This one’s about power, and it’s both advice (get strong yourself) and a threat (so as not to be overrun by those stronger than you).

Likely, this principle is the one that most ensnares us. Because there is always someone (or some thing) with more might, more money, more influence, or behaving more aggressively than we are. Which can convince us that we — and the systems we create — need to become more powerful, too. Our continual striving, one-upping, our need to perform and be rewarded, to outshine, to reap the rewards — these patterns seep into our lives and undergird the systems we build and live by.

Yet no matter how high up the ladder of power we climb, we never reach a safe spot at the top. Until, finally, we recognize the ladder is leaning against a wall there’s no getting past.

Unless we change a fundamental principle. Unless we move away from our belief that with enough power, things will get better. And toward what spiritual leaders might call love or compassion.

Does this seem crazy? (It would have to me a few years back). If so, here’s food for thought (attributed to the 10th century German philosopher Nietzsche): “And those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

Let’s listen.

Michael Gordon is a retired professor at University of Michigan, and author of Doing Good With Money (offered freely with an act of kindness!).

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: How do you relate to the need for new principles for evolving our economic thinking? Can you share a personal story of a time you discovered new principles to make a non-incremental leap in your endeavor? What helps you listen deeply to discover new principles?

Add Your Reflection

10 Past Reflections

On Apr 17, 2024 Stream wrote :

The fitness that has aided my survival most was taught to me by Baba Hari Das. He told me silently that my "business" depended on my "social life". When I take time to really deeply connect with other humans and help in any way I am able, I have received all that I need.

Post Your Reply

On Apr 17, 2024 Gururaj wrote :

Instinctive assumption that I must compete with others for resources and , once I start accumulatung wealth, pander to greeds well beyond needs) .

Can anything be done from within this system ( inexorably leading to self destruction on a planetary scale) ? I liked some fairly new concepts like carbon credits and I have heard of "goodness" credit in a European country where credits are recorded for hours spent volunteering for elder care which can be redeemed later in kind. Can there be a mechanism to directly tax excess resource consumers and transfer benefits in a simple way to those being more considerate to nature and fellow humans ?

2 replies: Gururaj, Gururaj | Post Your Reply

On Apr 16, 2024 Walther DREHER wrote :

1 reply: Michelle | Post Your Reply

On Apr 12, 2024 Jagdish P Dave wrote :

1 reply: Michelle | Post Your Reply